Cloudy with a 100% Chance of Cloud

I recently remembered that my site, and blog is Called Define the Cloud. That realization led me to understand that I should probably write a cloudy blog from time to time. The time is now.

It's 2018 and most, if not all of the early cloud predictions have proven to be wrong. The battle of public vs. private, on-premises vs. off, etc. has died. The world as it sits now uses both, with no signs of that changing anytime soon. Cloud proved not to be universally cheaper, in fact it's more expensive in many cases, depending on a plethora of factors. That being said, public cloud adoption grew, and continues to grow, anyway. That's because the value isn't in the cost, it's in the technical agility. We're knee deep in a transition from IT as a cost center back to it's original position as a business and innovation enabler. The 13.76 white guys that sit in a Silicon Valley ivory tower making up buzzwords all day call this Digitization, or Digital Transformation.

Down here, it's our time. It's our time down here…

It’s also our time. Our time! Up there!

<rant>

This a very good thing. When we started buying servers and installing them in closets, literal closets, we did so as a business enabler. That email server replaced type written memos. That web server differentiated me from every company in my category still reliant solely on the Yellow Pages. In my first tech job I assisted with a conversion of analog hospital dictation systems to an amazing, brand-new technology that was capable of storing voice recordings digitally, today every time you pick up a phone your voice is transmitted digitally.

Over the next few years the innovation leveled out for the most part. Everyone had the basics, email, web, etc. That's when the shift occurred. IT moved from a budget we invested in for innovation and differentiation, to a bucket we bled money into to keep the lights on. This was no-good for anyone involved. CIOs started buying solely based on ROI metrics. Boil ROI down to it's base-level and what you get is 'I know I'm not going to move the needle, so how much money can you save me on what I'm doing right now.'

The shift back is needed, and good for basically everyone: IT practitioners, IT sales, vendors who can innovate, etc. Technology departments are getting new investment to innovate, and if they can't then the lines-of-business simply move around them. That's still additional money going into technology innovation.

</rant>

One of the more interesting things that's played out is not just that it's not all or nothing private vs. public, but it's also not all-in on one public cloud. The majority of companies are utilizing more than one public cloud in addition to their private resources. Here are some numbers from the Right Scale State of the Cloud 2018 report (feel free to choose your own numbers, this is simply an example from a reasonable source.) Original source: https://www.rightscale.com/lp/state-of-the-cloud.

- 81% of enterprises have a multi-cloud strategy

- Companies using almost 5 public and private clouds on average

- Public cloud adoption continues to climb, AWS leads, but Azure grows faster.

- Serverless increases penetration by 75%. (Serverless will probably be an upcoming blog topic. Spoiler alert, deep down under the covers, in places you don't talk about at dinner parties, there are servers!)

So the question becomes why multi-cloud? The answer is fairly simple, it's the same answer that brought us to today's version of hybrid-cloud with companies running apps in both private and public infrastructure. Because different tasks need different tools. In this case those tasks are apps, and those tools are infrastructure options.

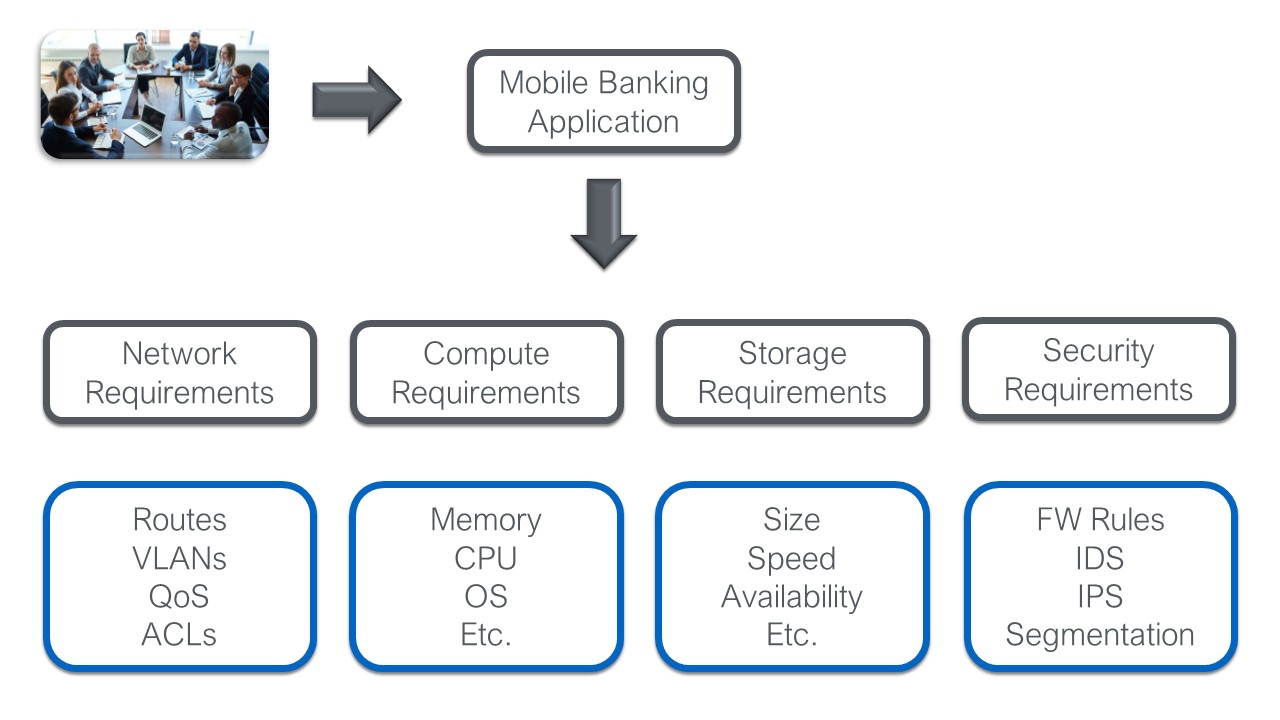

As an industry we chased our tails for quite a while around a crazy concept of 'Cloud Bursting' as the primary use-case for hybrid-cloud. That use case distracted us from looking at the problem more realistically. Different apps have different requirements, and different infrastructures might offer advantages based on those requirements. For more of my thoughts on cloud bursting see this old post: https://www.networkcomputing.com/cloud-infrastructure/hybrid-clouds-burst-bubble/2082848167.

Once we let that craptastic idea go we moved over to a few new and equally dumb concepts. The cloud doomsayers used a couple of public cloud outages to build FUD and people started fearing the stability of cloud. People of course jumped to the least rational, completely impractical solution they could: stretching apps across cloud providers for resiliency. Meanwhile those companies using cloud, who stayed up right through the cloud outages laughed, and wondered why people just didn't build stability into their apps using the tools the cloud provides. Things like multiple regions and zones are there for a reason. So some chased their tails a little on that idea. Startups started, got funded, and failed, etc., etc.

Finally we got to today, I rather like today. Today is a place where we can choose to use as many clouds as we want, and we're smart enough to make that decision based on the app itself, and typically keep that app in the place we chose, and only that place. Yay us!

Quick disclaimer: Not all multi-cloud came from brilliant planning. I'd take a guess that a solid majority of multi-cloud happened by accident. When cloud hit the market IT departments were sitting on static, legacy, silo'd infrastructure with slow, manual change-management. Getting new apps and services online could be measured in geological time. As organizations scrambled to figure out if/how/when to use cloud, their departments went around IT and started using cloud. They started generating revenue, and building innovation in the public cloud. Because they went out on their own, they picked the cloud or service that made sense for them. I think many organizations were simply handed a multi-cloud environment, but that doesn't make the concept bad.

Now for the fun part. How do you choose which clouds to use? Some of this will simply be dictated by what's already being used, so that parts easy. Beyond that, you probably already get that it won't be smart to open the flood gates and allow any and every cloud. So what we need is some sort of defined catalogue of services. Hmm, we could call that a service catalogue! Someone should start building that Service Now.

Luckily this is not a new concept, we've been assessing and offering multiple infrastructure services since way back in the way back. Airlines and banks often run applications on a mix of mainframe, UNIX, Linux, and Windows systems. Each of these provides pros, and cons, but they've built them into the set of infrastructure services they offer. Theoretically software to accomplish all of their computing needs could be built on one standardized operating system, but they've chosen not to based on the unique advantages/disadvantages for their organization.

The same thinking can be applied to multi-cloud offerings. In the most simple terms your goal should be to get as close to one offering (meaning one cloud, public or private) as possible. For the most part only startups will achieve an absolute one infrastructure goal, at least in the near term. They'll build everything in their cloud of choice until they hit some serious scale and have decisions to make. If you want to get super nit-picky, even they won't be at one because they'll be consuming several SaaS offerings for things like web-conferencing, collaboration, payroll, CRM, etc.

There's no need to stress if your existing app sprawl and diversity force you to offer a half-dozen or more clouds for now. What you want to focus on is picking two very important numbers:

- How many clouds will I offer to my organization now?

- How many clouds will I offer to my organization in five years? It should go without saying, but the answer to #1 should be >= the answer to #2 for all but the most remote use-cases.

With these answers in place the most important thing is sticking to your guns. Let's say you choose to deliver 5 clouds now (Private on DC 1 and DC 2, Azure, AWS, and GCP). You also decide that the five year plan is bringing that down to three clouds. Let's take a look at next steps with that example in mind.

You'll first want to be religious about maintaining a max of five offerings in the near term, without being so rigid you miss opportunities. One way to accomplish this is to put in place a set of quantifiable metrics to assess requests for an additional cloud service offering. Do this up-front. You can even add a subjective weight into this metric by having an assigned assessment group and letting them each provide a numeric personal rating and using the average of that rating along with other quantifiable metrics to come up with a score. Weigh that score against a pre-set minimum bar and you have your decision right there. In my current role we use a system just like this to assess new product offerings brought to us by our team or customers.

The next step is deciding how you'll whittle down three of the existing offerings over time. The lowest hanging fruit there is deciding whether you can exist with only one privately operated DC. The big factor here will be disaster recovery. If you still plan on running some business-critical apps in-house five years down the road, this is probably a negating factor. Off the bat that will mean private cloud stays two of your three. Let's assume that's the case.

That leaves you with the need to pick two of your existing cloud offerings to phase out over time. This is a harder decision. Here are several factors I'd weigh in:

- Cost, but be careful here. Costs change quick. Don't just look at the current costs, also weigh in the cost trends. In general cloud storage gets cheaper over time, while bandwidth and compute costs increase.

- Where the bulk of your public cloud apps live now.

- Feature set. Clouds have to differentiate to win customers, especially if the cloud isn't the incumbent (That means AWS, and does not mean I'm saying AWS doesn't innovate).

- Flexibility and portability. How restrictive are the offerings within the cloud of choice, and how hard would it be to migrate away at a theoretical point in the future. Chances are that will never be easy.

In the real world no decision will be perfect, but indecision itself is a decision, and the furthest from perfect. If you build a plan that makes the transition as smooth as possible over time, gather stake-holder buy-in, provide training etc., you'll silence a lot of the grumbling's. One way to do this is identifying internal champions for the offerings you choose. You'll typically have naturally occurring champions, people that love the offering and want to talk about it. Use them, arm them, enable them to help spread the word. The odds are that when properly incentivized and motivated your developers and app teams can work with any robust cloud offering you choose public or private. Humans have habits, and favorites, but we can learn and change. Well, not me, but I've heard that most humans can.

If you want to see some thoughts on how you can use intent-based automation to provide more multi-cloud portability check out my last blog: http://www.definethecloud.net/intent-all-of-the-things-the-power-of-end-to-end-intent/.